How To Protect Against Sequence of Returns Risk in Your Retirement Portfolio

Key Takeaways

- Sequence of Returns Risk has arguably the greatest influence on your potential retirement outcomes.

- Withdrawing money from your retirement portfolio in the presence of a negative sequence of returns can have a material adverse impact on your portfolio's longevity.

- You cannot eliminate Sequence of Returns Risk, but there are strategies that can substantially reduce the adverse impact a negative sequence of returns can have.

The transition from accumulation (or building savings) to decumulation (or living off of savings) presents an individual with many new risks that must be considered and managed before and throughout retirement. Among the many new risks (see "Evaluating the Big Five Retirement Risks Every Retiree Faces" for more), sequence of returns risk (SoRR) is arguably the greatest when it comes to the magnitude of the potential effect it can have on your retirement outcomes.

There’s a reason why many advisors caution against - and why we extensively write about - sequence of returns risk. Here, we explain what sequence of returns risk is, how we actively manage it for our clients, and a few tips on how you can protect yourself against its negative impact on your portfolio and retirement savings.

What is Sequence of Returns Risk?

When you’re in the “retirement red zone” and only a few years or months away from retirement, one of the greatest risks that you face is sequence of returns risk. We briefly wrote about this critical risk here, but it’s worth recapping the definition of the term before we explain how to protect against this risk.

Sequence of returns risk refers to the likelihood that a significant decline in your portfolio’s value, particularly early in retirement or just before it begins, could negatively impact the overall growth and performance of your investments. You can see an example of sequence of returns risk on a portfolio five years before and five years after retirement in our article Critical Risk During the Retirement Red Zone.

Magnitude of Threat Posed by Sequence of Returns Risk

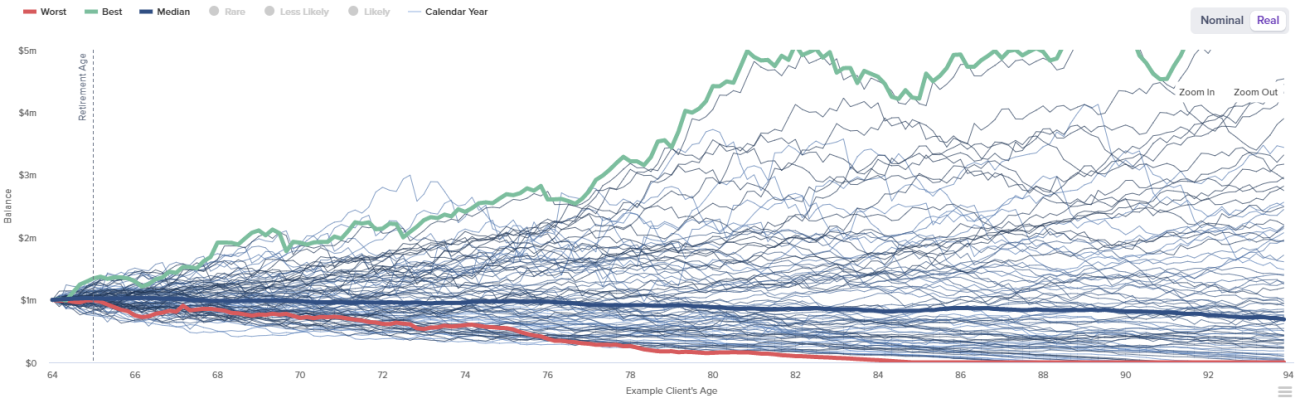

Just a quick peek inside of a Monte Carlo retirement planning simulation quickly highlights the magnitude of threat that sequence of returns risk can present a retirement portfolio:

This is a sample analysis for a retiree with $1 million dollars at the start of retirement at 64.

Each blue line represents a scenario subjected to a possible sequence of returns (i.e., a path of annual returns during an individual’s lifetime) based on actual historical observations.

The worst-case observation, indicated by the red line, represents a possible scenario where this hypothetical retiree would run out of money at age 84.

The best-case observation, indicated by the green line, represents a possible scenario where this hypothetical retiree would pass at 94 with $4.18 million (in today’s dollars).

These outcomes are considerably different, but each is a possible outcome based on historical observation.

Unfortunately, you cannot know the year-to-year sequence of returns you will experience during your lifetime. This is precisely the danger that sequence of returns risk poses on a retirement portfolio.

What we can do, however, is accept this unknown and have a game plan in place for how to react given whatever outcome is faced. When managing retirement withdrawals, it helps to understand the math behind sequences of returns risk to imagine the effect it can have on your portfolio.

You can also schedule a consultation with one of our retirement planning specialists to do the math for you through running a Monte Carlo analysis that will show you the potential outcomes for your portfolio.

Understanding The Math Behind Sequence of Returns Risk

From your high-school math class, you can probably recall the “Commutative Property of Multiplication,” which states that the order of the factors being multiplied does not change the product. For example, 12 x 3 = 36, and 3 x 12 = 36, too. It doesn’t matter whether the 12 or the 3 comes first in the equation.

Let’s further this example by having these numbers represent two different years of market returns. So, earning 12.0% in year one, followed by 3.0% the next year, would leave you with a 15.4% return over the two years. Even if we flipped the order of returns, the answer would still be 15.4% at the end of year two. The problem is that you don’t live off of percentages. (Nerdy side note – this is known as a Time Weighted Rate of Return, TWR, and is how money managers present performance to you). You live off of dollars.

What matters is not just the return earned but the amount of money to which the return was applied. Let’s continue to build on our example. Say you had $100,000 in year one and added another $100,000 at the beginning of year two. Now, you will see that the order of returns matters.

So 12% on $100,000 in year one is $12,000, and 3% on $212,000 in year two is $6,360, leaving you with $218,360 (or a gain of $18,360) at the end of year two. Now, let’s reverse the 12% and 3% returns. Earning 3% on $100,000 in year one is $3,000, and 12% on $203,000 in year two is $227,360 (or a gain of $27,360) at the end of year two. The second scenario yields $9,000 (or 49%) more return. The amount of money the return is applied to matters a great deal.

It's Your Timing of Outflows, Given Your Sequence of Returns, That Matter

Applying this math to a more real-world example, it becomes clear that a retiree's outcome has far less to do with the average return they experience over their retired lives and far more to do with the actual sequence of annual returns they experience being applied to their investment balance.

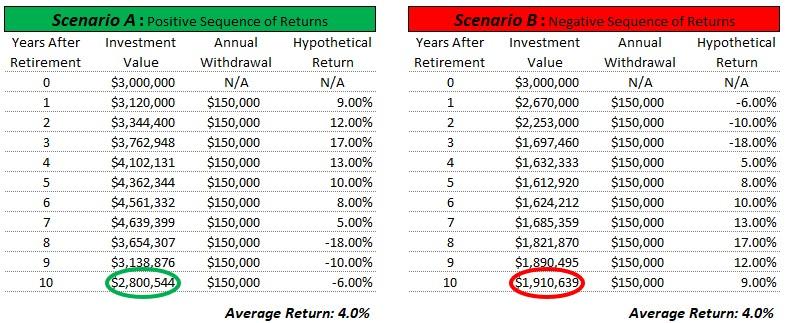

This can be seen in the example below, where two retirees both start with $3,000,000 and take $150k annual withdrawals but end up with very different remaining amounts after just ten years, given the exact same average return of 4.0% over the time period:

The retiree in Scenario B was irreparably harmed by continuing to withdraw $150k per year from assets that were down in value earlier in retirement. Not only did it take more assets to generate the $150k per year because of depressed market prices, but also those assets were gone from the portfolio and unable to participate in the ensuing market rebound. The timing of outflows under Scenario B in the presence of a negative sequence of returns had a material adverse impact on the retiree.

The Bad News: You Cannot Eliminate Sequence of Returns Risk

Because your particular sequence of returns is unknown, sequence of returns risk is ever-present. While we can never completely eliminate the risk, we can take actions to insulate you greatly from the harmful effects a poor sequence of returns can have.

Given the magnitude of the destructive effect mismanaging a poor sequence of returns can have, these strategies are worth their “weight in gold” when it comes to making sure you make the most of your situation, whatever is thrown at you.

The Good News: You Can Defend Against a Negative Sequence of Returns

Here’s how we go about managing sequence of returns risk for our clients in the near-term and in the intermediate-term.

Managing Sequence of Returns Risk in the Near-Term

Income laddering is our primary tool to mitigate sequence of returns risk in the near term. Income laddering is a strategy that structures investments to provide a steady stream of income over time, aligning payouts with specific financial needs or retirement goals.

Generally speaking, as individuals approach retirement, they should look for a good time to begin laddering approximately 12 to 24 months of living expenses (the exact duration depends upon individual circumstances).

Our best tool (given the yield environment today) to ladder income for a 12 to 24-month time frame is most often non-callable CDs or U.S. treasuries in three-month increments (typically, CDs offer slightly higher yields and provide greater flexibility).

When the CD on the bottom of the income ladder matures every three months, the proceeds are placed in a money market account to fund monthly “retirement paycheck” distributions to your operating checking account. When a CD matures, we would look to buy a new rung (or CD) at the top of the income ladder as long as markets are in good health.

You will experience many times during your retirement time horizon when markets will not be in good health.

Markets frequently fall in value (often steeply) in response to economic events (some lead to recession, some do not). When this happens, we pause buying new CDs. Recall we do not want to sell investments at a steep discount (i.e., have outflows during a negative sequence of returns event).

The good news under this strategy is that you will already have purchased 12 to 24 months of income, allowing you time to wait for markets to recover before resuming, thus insulating yourself greatly from the effects of a negative sequence of returns.

Managing Sequence of Returns Risk in the Intermediate-Term (and Emergencies)

Between April 1947 and April 2022, there were 14 bear markets, ranging in length from one month to 1.7 years, and in severity from a 20.6% to 51.9% drop in the S&P 500.

So what do you do if market values are still depressed but you run out of laddered income?

Here is where having a combination of savings buffer and/or short-term credit availability in the form of a Pledged Asset Line of Credit (PAL) or Home Equity Line of Credit (HELOC) comes into play.

Using idle savings is obvious, but using short-term credit is less obvious. The logic here is that it is much better to pay a little interest expense for a brief period of time than to sell assets off when markets are down steeply. When markets recover, you can liquidate investments to pay off whatever you borrowed under the line of credit.

A short-term line of credit is also an ideal source to mitigate “shock-spending” events.

What would you do if you suddenly had to come up with a large sum of money for some unpredictable (emergency) reason during a recession? A line of credit could be your savior here, too. Absent the line of credit, you would need to keep a larger savings buffer, which is essentially cash on the sideline not working for you (i.e., “cash-drag”) just in case a low-probability event occurs.

Sequence of Returns Risk Management Strategies Must Be Fine-Tuned to the Individual

These are the primary broad strategies we use to help our clients actively manage negative sequence of return risk events. The level and mix of these strategies must be fine-tuned for each individual to be optimized.

Following these strategies can substantially narrow the range of possible outcomes from the wide range we saw in our early Monte Carlo analysis example of running out of money at age 84 to passing away at 94 with $4.18 million.

If you would like the help of a retirement planning specialist in setting up your plan to actively manage Sequence of Returns Risk, click here to get a complimentary Thrive Assessment and get started.